07.2025

O’Keefe and the Limits of Artistic Freedom:

When the Art Escapes the Artist.

I have long been fascinated by the life of Georgia O'Keeffe: her affair with photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz, the provocative nude photography that emerged from their relationship, her swift ascent in the art world through her flower paintings, and the Freudian interpretations they attracted—read as subconscious expressions of female sexuality. When O'Keeffe heard this feedback, she refuted it, firmly asserting that she simply wanted to paint flowers. She famously retorted, "They were talking about themselves, not me," suggesting that the critics were projecting their own desires. Shouldn't she, after all, know better than anyone what her paintings were about? Yet there was little she could do to push back against the overwhelmingly masculine and patriarchal art world.

This reflects a classic artistic dilemma: the moment an artwork is released into the world, it belongs to the eye of the beholder. It escapes the artist's control and morphs into something new, shaped by interpretation. There's beauty in that process—a kind of unspoken collaboration between creator and receiver. The magic often resides in this in-between space: a dialogue, a spark, a personal reaction with infinite variability.

The first time I encountered O'Keeffe's work, it resonated deeply. I too had a fascination with studying and capturing flora, shells, and other natural forms—objects I found aesthetically miraculous and endlessly inspiring. I didn't perceive any sexual subtext. When I later read those interpretations, I felt naive, even blind, and thought I should defer to the 'experts' who seemed better equipped to decode her work. Only later did I begin to question those interpretations—and grew more curious about O'Keeffe's original intent. Now, I wonder: does it matter? Why do we feel compelled to understand the context or uncover the artist's true intention before we allow ourselves to simply feel the work? I've noticed a tendency to intellectualize art first, as if understanding it conceptually is a prerequisite to appreciating it emotionally. As if there were a 'right' way to experience a piece of art, a hierarchy of value we must navigate to be able to distinguish good and bad art.

This tendency may stem from a long evolution in the history of art, culminating in the highly conceptual contemporary era—where works often require layers of insider knowledge, context, and references to be fully grasped. The discourse around art, especially in institutional or established gallery settings, often feels exclusive—an entre-soi, or conversation among the initiated. It becomes a marker of social status more than a genuine appreciation of the work and its process.

Western culture tends to prioritize rationalization over emotional sensitivity. The latter is often seen as a weakness, something outdated or primitive. In Descartes' Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain, neuroscientist Antonio Damasio reassesses the split between body and mind proposed by the 17th-century philosopher. He argues that reason cannot function without guidance from emotions, feelings, and sensory cues. Like children—or like my naive self, perhaps—our first contact with a piece of art should not be to seek its meaning, but to experience its feeling through our body and senses.

I recently watched the documentary Georgia O'Keeffe: The Brightness of Light, which offers a rich, detailed and comprehensive portrait of her life. I wanted to know more about her background and the enigma surrounding her motives. From the outset, her independence and strong sense of identity were evident, starting with the bold abstraction of her early charcoal drawings (mostly untitled) that first caught Stieglitz's attention in 1915–16.

O’Keefe’s charcoal drawings 1915-1916

Throughout her career, she continued to follow her instincts and paint what moved her, regardless of trends or the pressure to prove her uniqueness. She painted the "very lively" flowers, seashells, and bones she found in New York’s countryside, Texas, and later New Mexico, guided by personal inspiration. It seemed that many of her (mostly male) peers could not accept the 'simplicity' of her work and sought instead to analyze it in ways that confirmed their worldview. This didn't deter her. "I don't mind [my work] being pretty," she claimed—asserting both her freedom from contemporary standards and her indifference to external judgment. One could argue that observing and honoring nature in such a dedicated, almost spiritual way could also be considered as the grandest artistic approach possible.

From left to right: Pink shell 1931, Light of Iris, 1924, Flower of Life II, 1925, by O’Keefe

In her essay Peindre au Corps à Corps (not yet translated into English), Professor Estelle Zhong Mengual analyzes how O'Keeffe's work has been interpreted and offers a fresh perspective. She argues that flowers are not just fragile or pretty but are foundational to life. Paraphrasing her essay, Zhong Mengual critiques the tendency of critics and upper classes to over-intellectualize art as a way to distinguish themselves from lower classes. Referencing sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, she describes this as a preference for "the pleasure of decoding" over "the immediacy of received experience."

Zhong Mengual then draws on philosopher Baptiste Morizot’s perspectivist theories, which argue that perception is relative to the perceiver’s capacities—especially across species. Her thesis is fascinating: She invites us to imagine seeing O'Keeffe’s flowers not as humans, but as insects drawn to pollinate them. We are absorbed like magnets into the painting, and we see flowers for ‘what they really are’, monumental, alive, essential. Not symbolic objects for humans, but vibrant organisms central to Earth's ecosystems.

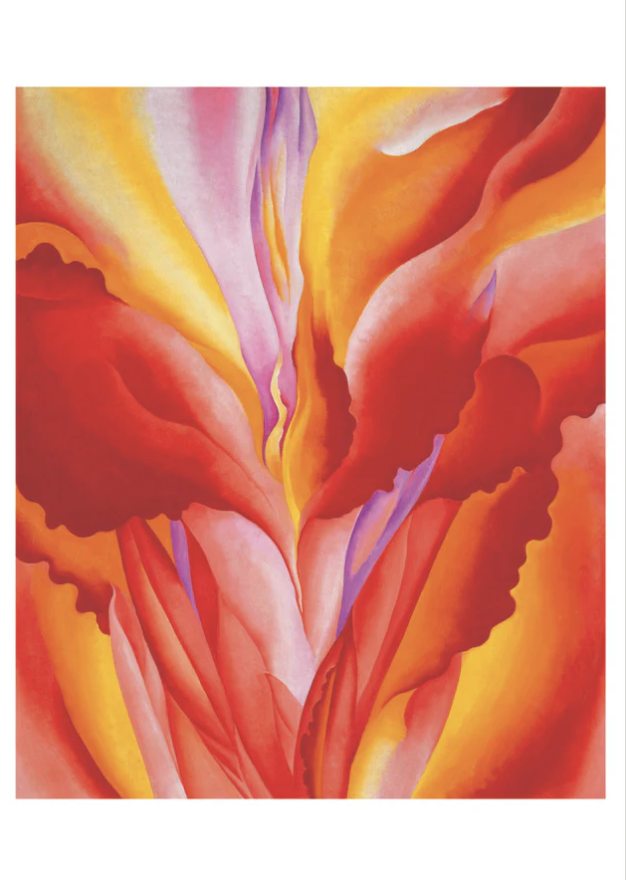

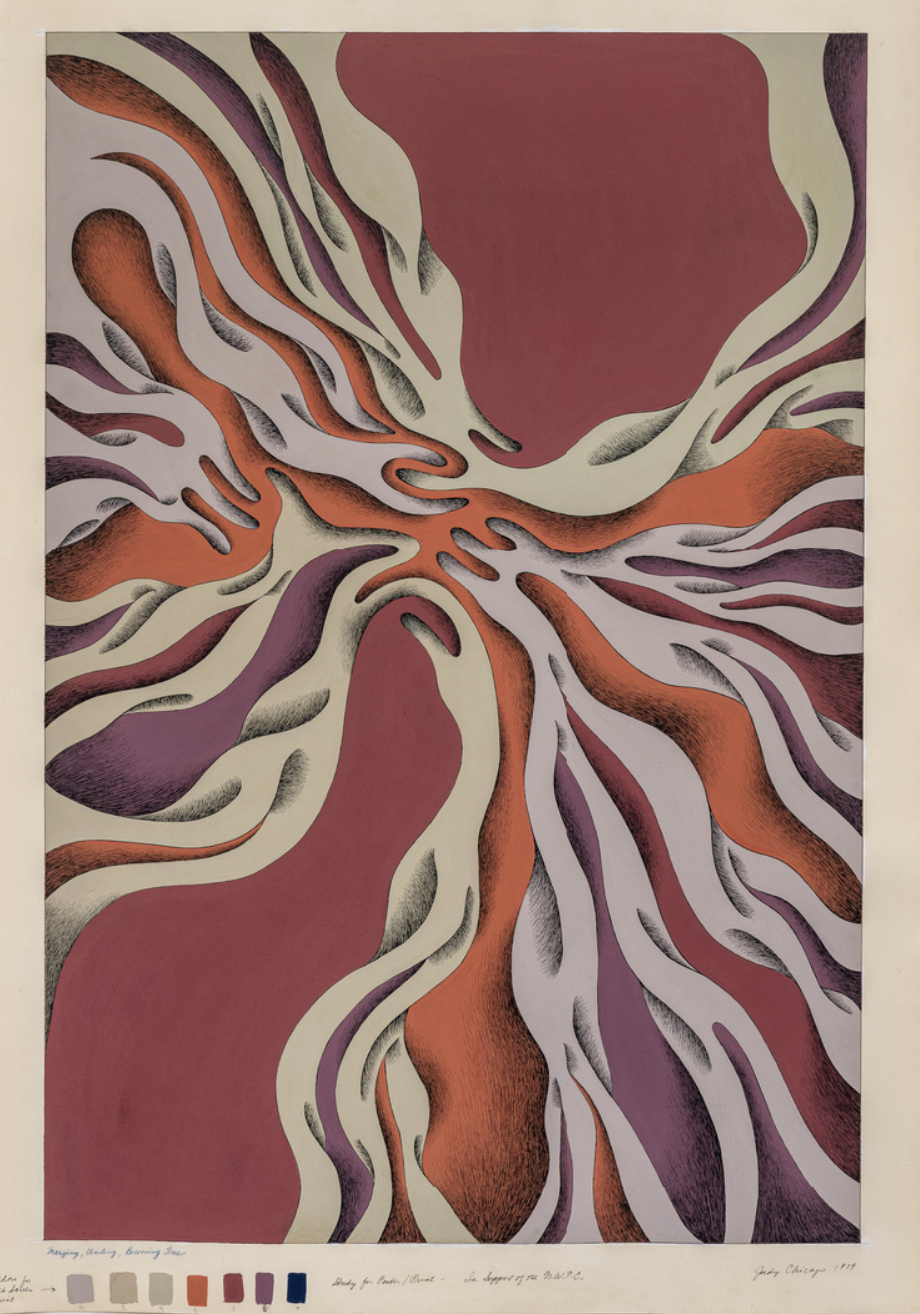

The Brightness of Light documentary also explores how interpretation can diverge across gender and generations. Judy Chicago, for instance, saw herself reflected in O'Keeffe's art. She was part of a generation that valued collective feminist action and created space for women artists by foregrounding activism. O'Keeffe, by contrast, did not embrace the feminist framing of her work. She wanted to be seen as an artist, not a woman artist. She was part of a generation that championed individualism and modeled a sense of quiet confidence with deep belief in her work. Putting the work of both artists next to each other, there is an undeniable lineage, the sacred geometry, the vibrancy of the colors, the organic abstraction, something she couldn’t have anticipated or controlled. And yet, despite herself, she became an icon of a movement she did not claim, and paved the way for the other female artists.

From left to right: Music Pink and Blue II, O’Keefe; Rejection Fantasy Drawing, from the Rejection Quintet, Judy Chicago 1974; Red Cana, O’Keefe, 1923; Reaching / Uniting / Becoming Free, Judy Chicago, 1979

The more I discover O'Keeffe's work, the more connections I find—like breadcrumbs left behind. One recurring motif is the spiral, appearing subtly in natural forms or boldly in landscapes and early watercolors. It shows up in her handwriting, in a large sculpture, and in her signature, which Alexander Calder turned into a brooch that she proudly wore in portraits. The spiral is rich in symbolic meaning—perhaps referencing cycles of life, personal journeys, or simply a hypnotic device to hold the viewers in the present moment, leaving them to project whatever meaning we’d like to attribute, knowing all along that it would escape her. This is all of course pure speculation.

From left to right: Watercolor, Evening Star No. IV, O’Keefe 1917; Carl Van Vechten, Portrait of Georgia O'Keeffe, Abiquiu, New Mexico, 1950; O’Keefe’s Brooch by Calder; letter to Henwar Rodakiewicz from 1936, written by Georgia O'Keeffe

Ultimately, what inspires me most in O'Keeffe's work is something primal and intuitive—something close to magic. I’ve noticed that when it comes to art making, no matter how brilliant an idea may be, if the translation from concept to artifact is missing, I struggle to connect. For me, the power of art lies in its ability to communicate a feeling that can't be conveyed any other way. That’s the craft an artist spends a lifetime developing—a voice so personal that only they could speak it. Art doesn’t need to offer answers; it invites connection, whether it stirs conflict or resonance. In O'Keeffe's case, that connection lies in her mastery of form and color, her unique perspective, and the sheer sensory pleasure her work evokes. In that quiet contemplation, we are invited into a space that belongs to us as much as it did to her—a space where meaning is not dictated, but ours to discover.